April 28, 2020

IUPUI's Carmen Luca Sugawara, an associate professor in the School of Social Work, was completing a prestigious Fulbright program in Croatia when COVID-19 began spreading across the world.

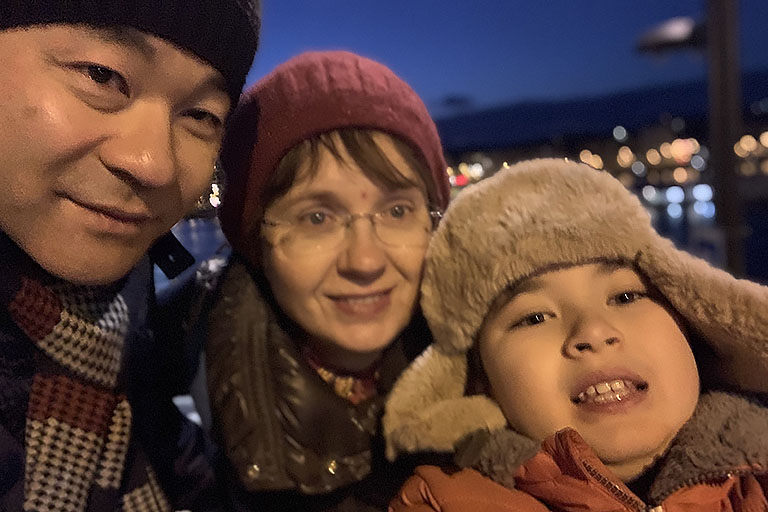

When she arrived in Zagreb on September 1 as a Senior Fulbright Scholar, she was excited to embark on a nine-month sabbatical with her family in tow. She never could have predicted a global pandemic would occur or that a 5.3 magnitude earthquake would hit during social distancing, causing $6 billion in damage and forcing the family to relocate.

Currently, Luca Sugawara remains in Croatia, where she shared her family’s experience dealing with the pandemic while being so far from home.

Tell us about your Fulbright scholarship.

As a Fulbright Scholar and social development researcher, I was enthusiastic to start a new research project that examined how higher education community-engaged programs contribute to building local capacity for community development in post-communist countries. As an international educator, I was thrilled to engage with Croatian students and faculty of social work in various teaching opportunities and curricula development initiatives. As a mother and wife, I was excited to begin a new journey of living life in a country known for its communitarianism, joyous coffee culture, and vibrant social networks.

I had been working in this part of the world for more than a decade. Throughout the years, I recognized the strong capacity that existed in both the civil society sector and the university and lamented the continued disconnect between Croatian universities and local community groups.

At the University of Osijek, I committed to join their local efforts and support the development of a much-needed MSW program in this post-war region, in addition to pursing teaching opportunities while furthering our community-engaged, capacity-building efforts with local partners to help the university and community organizations strengthen synergies and work together. At the University of Zagreb, I engaged in various teaching opportunities on topics of international social work and community development, in addition to making Zagreb a hub location for my research project.

What has it been like dealing with the pandemic in Croatia?

The social health behavior in Croatia is very different from what I see happening in the US, and perhaps even other countries in Europe. Some local scholars attribute this to the Homeland War of the 1990s, with social distancing recalling memories of wartime. During such trying times, Croatian communities learned not only to survive, but to develop behavior patterns to adapt and respond to human threats. This perhaps gave Croatians the discipline to follow the protective rules for themselves, their loved ones, and their communities.

The community social structures are slowly resurfacing in Croatian day-to-day lives, reminding local citizens they aren’t alone. Gardeners are delivering veggies to local neighborhoods, and young people are leaving notes on the elderly’s doors offering support. This is inspirational!

How has your family coped?

With the increasing crisis in neighboring Italy, Croatia was faced with the danger of having many Italians crossing borders, prompting the government to shut borders quickly. Because of this, coupled with the ongoing broadcasting of governmental messages and the development of a public health response mechanism with designated locations for testing, quarantine hospitalization locations, and social distancing measures, the fear of the pandemic wasn’t a threat to our family.

We stayed informed, followed protocols, and were preparing ourselves for sheltering for an unknown time. There wasn’t fear, but more of a slight anxiety coming from the unpredictability of the pandemic and its long-term impact on my research and our possible stay abroad.

On March 13, the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs sent an email strongly advising us to return home. It was a recommendation, but if the embassy were to evacuate, we had to leave. That news was devastating. The fear of having to fly across an ocean at the time of the pandemic, putting my family in harm’s way, was keeping me awake at night.

As a social work scholar who understands protective measures and institutional polices, I knew I had to advocate for my family and asked to be involved in the decision-making process about our safety. At no time in my life have I felt as powerless as I did that week. Knowing a system was deciding my family’s health without understanding our context was concerning. I wrote a letter to the U.S. Embassy on March 18 kindly requesting to remain in Zagreb under the current social distancing rules until the pandemic subsides or the end of the Fulbright grant, whichever came first.

After daily conversations with an extraordinary U.S. Embassy team, I received an email on March 20 from the U.S. Ambassador of Croatia, Robert Kohorst, authorizing us to seek shelter in Croatia until June 30, 2020. This news brought much peace to our hearts. All we had to do now was stay safe, follow the social health protocols, and maintain an in-house routine that would bring joy and memorable family time. We started doing in-house exercises, spent more time playing board games and watching movies, reading, and having long evening talks with lots of laughter. This new lifestyle lasted only one day.

A 5.3 magnitude earthquake hit Zagreb on March 22. What was that experience like?

I was awoken at 6:25 am by the most frightening, howling sound I have ever heard, with the earth shaking beneath us. I ran to the stairs to grab our son from bed, but they were shaking to the point I couldn’t advance. I started calling his name as loudly as possible, asking him to wake up and reach my hand. I could see the walls above us cracking, and pieces of the concrete were falling on his bed. All I wanted was to make it there and shield him with my body.

The earthquake lasted approximately 10 seconds before I managed to reach him. We ran to the living room where my 71-year-old mother had her hand at her heart, and my husband was trying to comfort her. The earth started moving again, a 3.9 magnitude this time. After a few more aftershocks, we decided to leave the apartment, fearing a possible building collapse.

Our desire to survive the imminent threat of yet another earthquake superseded the fear of contamination of the coronavirus. We buckled up, took our passports and cash and made it through the damaged hallways to seek shelter in a nearby park. People looked fearful, but they were concerned for one another. A young man came to us, asking to reposition our bodies against the wind to protect us from possible airborne coronavirus contamination.

As we started exploring new long-term housing, we found ourselves facing a challenge that was becoming a threat to local communities: foreigners seeking shelter during the pandemic. To overcome this, our local friends started connecting us to real estate assets in Zagreb, and we were able to find our current apartment.

How was your research affected by COVID-19?

Continuing my research project at a time when the community was shaken by an earthquake and pandemic was practically impossible. Everyone is focused on using all resources (including time and creativity) to respond to imminent local community needs, to support social structures, and to alleviate human suffering. Finding answers to research questions that did not connect directly with earthquake and coronavirus responses felt like a distraction from what was important – the well-being of local communities. Therefore, I decided to alter the approach to data collection and extend some research timelines.

What have you learned from this experience?

More than ever before, I see the importance of investing in community-engaged education. Building our educational infrastructures to anchor our students’ learning in the community is without a doubt, key to the success of our students, and the strengths of our communities. The very gift of community-engaged education rests in the synergies developed between the academic units and the very communities we serve in facilitating partnership development, the growth of social capital, and the community’s readiness to respond in unity and with strengths, when human communities are threatened.

Throughout our experiences, there were great lessons learned about our personal vulnerabilities and strengths. I also learned first-hand that the resilience of our lives is influenced by the strengths of our own communities. The ability to walk through natural disasters or a pandemic is a collective experience. One’s resilience depends on the social networks and local resources readily available for its community members.

Our friends, our family members, our colleagues and neighbors that make up our communities are the first responders, and the most important ones in aiding our psychosocial needs at this time of distress. When my dean, Tamara Davis, was finally able to reach me, being concerned about our safety and asking what the school could do for us, it gave us so much comfort. We knew we were not alone.

We are staying positive and in shelter and hoping this pandemic will pass soon. Our meaning of home has changed, and our sense of gratitude has new understandings. We thank the Croatian communities and friends for harboring us in their hearts, and in their homes, during these trying times.

We also want to thank the entire IU community from the Berlin Gateway to Indiana, who took the time to check on us, giving us a deep sense of belonging to an academic community that I very much miss right now. We cannot wait to go home to Indiana University.