In the United States, immigration has long been a topic of debate, and now that debate is perhaps more polarizing than ever before.

With threats against Asian Americans on the rise and an ongoing crisis at the southern border, IUPUI anthropologist Susan Hyatt hopes to shed light on today's immigration challenges by studying immigrants of the past – specifically, Jewish immigrants who arrived in Indianapolis and in the US during the early decades of the 20th century.

For the last decade, Hyatt has worked with her students on an oral history project recording interviews and doing archival research on a southside Indianapolis neighborhood that once fostered lasting relationships between Jewish immigrants and African Americans, even at the height of Jim Crow segregation.

It was through that work that she became interested in the stories of how Jewish immigrants had arrived in Indianapolis in the first place, and she began to examine the experiences and challenges Jewish immigrants encountered as they left their home countries and arrived in Indianapolis – something Hyatt says is relatable to what many immigrants are experiencing now.

“Immigration is a very fraught and difficult process, especially when people feel forced to leave their homelands for whatever reasons,” Hyatt said. “Some of the public discussion today about immigrants who are coming from Latin America, Africa and Asia implies that non-European immigrants are less able to ‘fit in’ and to adjust to life in the US. We are discovering that Jewish immigrants faced similar challenges 100 years ago and similar accusations were leveled at them, as well as at other European immigrants.”

Through their research, which is supported by IU’s Racial Justice Research Fund, Hyatt and her students are challenging the current myth that immigration from Europe was any less fraught or difficult than the hardships immigrants face today.

“By tackling immigration from this historical context, we are hoping to reach people who may share these negative assumptions about contemporary immigrants,” said Samantha Riley, who is pursuing a Master’s in Applied Anthropology at IUPUI. “Revealing some of the stories about immigrants of the past helps to contest the idea that their adjustment to American life was without problems.”

Hyatt has uncovered many interesting accounts of how some Jewish Hoosiers initially arrived in Indianapolis. One way was through the actions of an agency called the Industrial Removal Office. Established in New York at the turn of the 20th century by highly assimilated German Jews, its goal was to prevent large numbers of Jewish immigrants arriving from southern and eastern Europe from congregating on the east coast. The Industrial Removal Office thought that sending these new arrivals to other parts of the country would reduce their visibility in big cities, thereby reducing the likelihood that they would provoke outbursts of anti-Semitism.

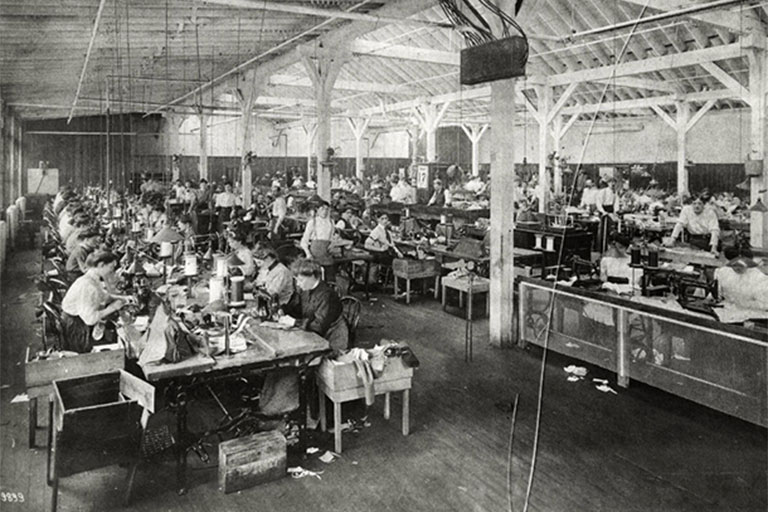

While conducting research at the Indiana Historical Society, Hyatt uncovered telegrams between the Industrial Removal Office and an Indianapolis-based clothing company called Kahn Tailoring, which was a nationally known manufacturer of men’s suits and produced uniforms for the US army during World Wars I and II. They recruited immigrants experienced in the needle trades to come to Indianapolis, positions they often filled with many individuals who had fled Europe following the upheaval of World War I.

Hyatt found further evidence the Industrial Removal Office played a role in relocating Jews to Indianapolis in interviews with Jewish elders from the southside neighborhood, with many sharing their belief that their parents had arrived around the time of World War I, “sent by an agency in New York.”

While examining the historic records of the Indianapolis Jewish Welfare Federation, Hyatt and her students discovered many stories of people who sought help when the challenges of immigration became too difficult. Many dealt with job loss or illness and injury. And for women, a common theme was desertion. There were cases of men arriving to the US first, intending then to send for their wives and children after they were established. But when the wives arrived from Europe, they often discovered their husbands had set up households with new families, abandoning these women to fend for themselves. This became such a prevalent issue that a National Desertion Bureau was founded in 1905 to help Jewish women who had been deserted by their husbands.

Hyatt and her students also hope to challenge the long-standing idea that immigrants coming to the United States need to completely assimilate as quickly as possible in order to be successful members of society.

“It’s important to share these long and complicated histories and to think critically about how our country has been influenced by all of these groups,” Hyatt said. “Take Indianapolis, for example. When we think about the landscape of the city, some very notable Jewish families really helped create the city that we see today. Many of their parents and grandparents arrived here in the early decades of the 20th century, penniless and facing a range of issues, including poverty and anti-Semitism.”

While the pandemic has hindered their ability to meet with Indianapolis families in-person over the last year, Hyatt and Riley plan to continue working to uncover the histories of Jewish immigrants to Indiana. They hope to visit Jewish cemeteries and towns in Indiana where people once settled. When travel becomes possible, Hyatt would like to examine records from the Industrial Removal Office which are now housed in New York to find even more connections to Indianapolis. Hyatt and Riley hope to share some of these stories through a blog, which will make them accessible to more people.

“It is always instructive to examine the challenges and roadblocks that people in the past faced,” Hyatt said. “It prevents us from romanticizing our own history and helps us remember that the US is always being shaped and reshaped by the remarkable contributions and determination of all of our immigrant communities, both those who arrived here in the past and those who continue to seek out new opportunities here today.”