March 31, 2020

When IU postdoc Daniella Chusyd was preparing to spend a year conducting field research in forests throughout Africa, her thoughts were on operational aspects of the trip like what supplies she would need, how to get to her destination and how she would adapt to living in very remote areas.

But two months into her trip, Chusyd biggest concern ended up being a scramble to return back to the states in the midst of worst pandemic in a century.

“I never would have guessed this would be the situation,” said Chusyd, a postdoc fellow in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the School of Public Health-Bloomington. “When friends started talking about the coronavirus in the states, I wasn’t worried about it. I was thinking it wouldn’t touch me in Africa. This was before I realized how big it would get and the global and far reaching impact it would have.”

Chusyd’s trip abroad began in January 2020, with plans to work in the Congo, Uganda, Zambia, and South Africa through January 2021. Her work focuses on elephant health and reproduction, and she is working to demonstrate the value of using the elephant as a model for determinants of human aging, including how early life trauma associates with health.

The first part of her trip included the Congo, where Chusyd, along with 14 other people, was working and living in an isolated area with no electricity or running water, limited access to the internet, and accessible only by a 45-minute canoe ride and a two-day travel away from Brazzaville, the capitol of the Congo and nearest international airport.

When cases of COVID-19 began to spread, Chusyd received updates from her family and friends via text. Like many people throughout the world, at first Chusyd didn’t understand the severity of the virus. Working in such a remote area also reinforced the idea the virus wouldn’t reach her.

Chusyd had plans to start the second part of her research journey on March 26, which would have taken her to Uganda. There were no COVID-19 cases in her area or most of Africa at that time. A call to the U.S. Embassy didn’t raise any concerns so Chusyd thought she would hunker down in Uganda until things blew over.

But as the virus quickly spread, things began to change. The Wildlife Conservation Society, which runs the field site Chusyd was working in, strongly recommended nonessential staff return to their home country. Her family, friends, colleagues at IU, and others in the field also started suggesting Chusyd come home. In a matter of days, flights began to cancel, and countries began closing their borders.

It wasn’t necessarily the fear of contracting the virus that worried Chusyd, she said, but the idea that if an outbreak were to happen in the isolated area she was working in, it would take days for her to make it to a medical facility. She also worried about her safety if the area became unstable due to a lack of supplies or medical availability.

“In the span of four or five hours, I went from looking at travel options for Uganda to start the next leg of my journey to ‘I need to find a flight back home,’” Chusyd said. “Everything happened so quickly and changed so fast. Things were changing by the minute. It was unbelievable.”

Once Chusyd made the difficult decision to leave Africa – a part of her still hung on to the chance she might wait it out – getting a flight out of the continent was a whirlwind.

Chusyd enlisted the help of her mother in Florida, her sister in Washington D.C., and a friend at the State Department who helped update her on the rapid changes occurring. She also had the help of Indiana University leadership. One of those leaders was David Allison, dean of the School of Public Health-Bloomington, who had been keeping in touch with Chusyd during her trip.

Although the School of Public Health had other faculty working abroad, Chusyd’s situation was different, Allison said, due to the isolated nature of her location and the potential for things to take a turn for the worst if the area became unsettled.

“Although we were concerned about the virus itself, our biggest concern was what could happen secondary to the virus,” Allison said.

With help from others, Chusyd began looking for commercial flights—there was no emergency air evacuation taking place.

While plans started off “business as usual” – Chusyd would travel to the city, book a flight, and head home – the rapidly changing nature of the virus made things more difficult, rattling the nerves of those back home.

“When she got to the city and planes were being canceled and borders were closed, we started to get anxious,” Allison said. “We started wondering ‘would we be able to get her home?’”

Allison worked with others at IU including Shawn Gibbs, executive associate dean and an expert in infectious disease; Colby Vorland, postdoc and friend of Chusyd; Michael Wasserman, assistant professor in anthropology; Fred Cate, vice president for research; and Bill Stephan, vice president for engagement.

Together, the group, along with Chusyd’s family, worked around the clock with the researcher and IU friends and alumni—including staff in the office of Vice President Mike Pence; former NORAD/NORTHCOM commander General Gene Renuart (ret’d) and his son, Ryan, who works at the State Department; Army Intelligence Colonel H.A. Boyd (ret’d); and the staff at Classic Escapes, who organize travel in Africa for the Indianapolis Zoo—to help her make it home.

Over the next few days, Chusyd booked six different flights in her attempt to get home. Finally, she got some good news from a colleague. There was a flight leaving Rwanda on March 21, and it would be the last flight out of the country. Chusyd and a fellow researcher, who was also doing work in the region and was looking to go home, jumped at the chance. But they weren’t sure they actually would make it to Rwanda.

During the two days it takes to make it to Brazzaville from their field site, Chusyd and her colleague were told the flight from the Congo probably wouldn’t leave the ground, and they should be prepared to be stuck in Brazzaville for the next 30 days. So when they got to the airport and saw the plane pulling up to the gate, they were ecstatic.

“We started laughing and pointing,” she said. “We were like kids at Disney.”

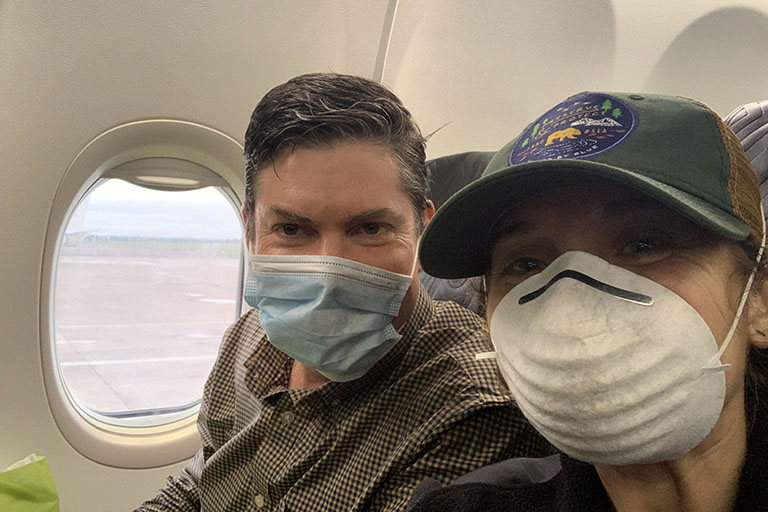

They made it to Rwanda, taking not only the last flight out of the Congo but also the last flight out of Rwanda.

As she currently quarantines at a friend’s home, Chusyd feels lucky. Not only did she make it home, but she still has a Congolese colleague is who able to continue to collect data for her research project, and she is hopeful she will be back in Africa sometime this year to continue her work.

She also is thankful for all of the people who worked tirelessly to keep her safe and return her home.

“I’d call my mom, sister, and a friend, with news that another airline was suspending flights, or a country was closing their borders and I needed a new flight, and they would immediately drop everything and hop on the computer and look for new flights for me,” Chusyd said. “Dean Allison and my co-mentor Mike Wasserman were regularly in contact with me, providing me with advice and trying to move mountains back here. Then, of course, Fred Cate. He went above and beyond, using his contacts to make sure I got back home. I’m beyond grateful for all their actions, but also, it just showed how much everyone cares.”